FUTURE OF FLIGHT • September 2020

How hydrogen could fuel aircraft of the future

Aviation aspires to become emission free. Electric, biofuel and synthetic energy sources will all play a role in that future, but what about little ol’ hydrogen? Aero-industry journalist Paul Sillers takes a look at its increasing promise as a viable fuel for aviation’s decarbonisation

As air travel gets going again, the drive for a ‘Green Recovery’ means that all avenues for cleaner aircraft energy sources – and those that can make our airports greener, too – are being explored.

Synthetic fuels and biofuels will be a part of aviation’s ecological shift – and British Airways is already playing a role towards this, thanks to a collaboration with Shell and Velocys’ subsidiary Altalto to develop the UK’s first commercial waste-to-jet-fuel plant. The idea is to convert annually half a million tonnes of non-recyclable coffee cups, food packaging and even nappies into clean-burning jet fuel.

Sustainable biofuels will be complemented by the rise of electric aviation, especially as urban aerial mobility – mainly in the form of flying taxis, or VTOLs – begin to start up. Excitingly, some of these are already undergoing test-flights.

But there’s another fuel source being investigated for use in aviation that rarely hits the media radar: hydrogen.

Why hydrogen?

The lightest element in the Periodic Table, hydrogen packs much more of a punch than the equivalent weight in electric batteries, and it also has an energy density three times that of regular jet fuel. And the other benefit is that hydrogen, as a fuel, doesn’t contain carbon – so its combustion does not cause CO2 emissions.

“The additional cost of using hydrogen instead of regular jet fuel would be around £15 extra per person on a short-range flight.”

A recent study (published by Clean Sky 2 and Fuel Cells & Hydrogen 2 JU) on hydrogen’s potential for use in aviation concluded that “novel and disruptive aircraft, aero-engine and systems innovations in combination with hydrogen technologies can help reduce global warming effects of flying by 50 to 90 per cent.”

The study estimates that the additional cost of using hydrogen instead of regular jet fuel would be around £15 extra per person on a short-range flight. A small price to pay for such a considerable environmental gain.

But further research and development into hydrogen fuel cell technology and liquid hydrogen storage is needed. Also required is investment in fleet and hydrogen infrastructure, plus new regulations and certification standards to ensure safety, reliability and economic viability.

ZeroAvia recently conducted a successful test flight, establishing a roadmap for UK Government-funded hydrogen-powered aviation

Ready for take-off

An initiative under way to exploit the energy-to-weight-ratio of hydrogen fuel is HyFlyer, a UK Government-backed project funded through Innovate UK and the Aerospace Technology Institute (ATI). The project, led by ZeroAvia – a company focused on the design and commercialisation of hydrogen-powered aviation solutions – aims to develop a hydrogen-powered short-haul ten-to-20-seat airplane for commercial flights of up to 500 miles.

This June, ZeroAvia carried out the first successful HyFlyer test flight from Cranfield airstrip in a Piper M-class six-seater aircraft, representing an important milestone in the development of a hydrogen-electric powertrain for aircraft.

“We all want the aviation industry to come back after the pandemic on a firm footing to be able to move to a net zero future, with a green recovery,” says Val Miftakhov, ZeroAvia founder and CEO. “That will not be possible without realistic, commercial options for zero-emission flight, something we will bring to market as early as 2023.”

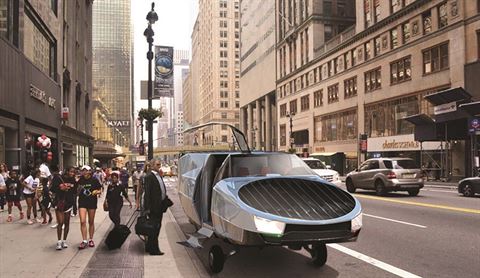

Urban Aeronautics’ CityHawk VTOL could whisk up to five passengers across the city, powered by hydrogen fuel

What might hydrogen-powered planes look – and sound – like?

One of the environmental challenges for any type of urban flying machine is noise. VTOL maker Urban Aeronautics aims to address this and other challenges with its CityHawk, a hydrogen-powered flying vehicle that can be configured as an air taxi for four to five passengers, a private flying car or an emergency response vehicle for medical evacuations.

The CityHawk’s propellers are buried within the fuselage, which acts as a muffler. Urban Aeronautics says that its CityHawk prototype already generates much less noise than a helicopter. And in its production model the company intends to increase the number of propeller blades and decrease their rotation speed. This, it says, “will reduce noise level to 70 decibels, the sound of current day street traffic.”

If all goes to plan, Urban Aeronautics hopes that the first people-carrying flights of CityHawk will begin in 2022, to be followed by full commercial FAA certification.

Pipistrel’s UNIFIER19, a 19-seater that uses liquid hydrogen hybrid propulsion technology, could be a stepping stone to medium-sized hydrogen-powered airplanes

In Slovenia, planemaker Pipistrel is working in partnership with Politecnico di Milano and TU Delft on a ‘zero emission 19-seat commuter aircraft’ called UNIFIER19. The design programme involves focusing on hydrogen and hybrid propulsion technology.

“By using hydrogen-based propulsion a 100 per cent emission reduction is expected,” says the company. “Apart from the emission reduction potential on the aircraft level, the aircraft will present a stepping-stone for using zero emission technology on larger platforms.”

Fuelling up

Today’s aviation relies on long-established kerosene pipelines. How will hydrogen-powered airplanes access the fuel supplies they need?

“HES Energy Systems aim to make hydrogen-powered aerial vehicles a reality in the next decade.”

Singapore-based HES Energy Systems (H3 Dynamics Group), a developer of high performance airborne hydrogen fuel cell propulsion systems, has been progressing its Element One Aviation initiative with a global alliance of technology partners and universities, aiming to make hydrogen-powered aerial vehicles and their fuel infrastructure a reality in the next decade.

“Airports are logistics and transportation hubs where several modes of transport meet: trains, cars, trucks, buses, aircraft, forklifts, and bikes,” the company’s product manager Bertrand Gauthier tells The Club. “These are set to become energy hubs where energy can be locally harvested, transformed, stored and distributed.”

HES Energy Systems intends “to develop a network of hydrogen airbases for autonomous long-range hydrogen drones and aircraft.” (HES/H3 Dynamics Group)

Gauthier adds, “The main advantage of hydrogen is its capacity to store energy for a long time in large quantities and to fuel low-carbon emission lightweight electric vehicles and equipment.”

As airports strive to become carbon-neutral, with increased focus on energy management, he says, “Some airports have expressed their willingness to support our initiative to build a network of hydrogen-ready hubs that would facilitate the deployment of new ground and aerial vehicles.”

But what about bigger airplanes?

All these exciting developments are clearly focused – at least for the moment – on relatively small-scale airplanes. Could hydrogen really be used for medium and long-haul flights? The world’s two biggest airplane builders appear to think so.

Airbus chief technology officer Grazia Vittadini said recently that Airbus has “opened up inquiry into new technology pathways, hydrogen being one of them, which is equal parts a huge opportunity and a new challenge.” The company says that it considers “hydrogen to be an important technology pathway to achieve our ambition of bringing a zero-emission commercial aircraft to market by 2035.”

In the US, Boeing recently funded and released a report entitled ‘Opportunities for hydrogen in commercial aviation’, authored by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO).

The report says: “Growing hydrogen industry momentum could provide an opportunity to introduce hydrogen for niche airport applications (such as ground support equipment) as early as 2025.”

In the meantime, with industry players now in a race to harness the unique and ecological power of hydrogen, it’s most certainly the one to watch.

This article has been tagged BA, Technology

More from previous issues

Stylish sleeps: the hotels for your next getaway

Find out where the world’s leading architects lay their visionary heads with our round-up of some of their favourite hotels

The eStore’s guide to the Caribbean

If you’re yearning for winter sun and those barefoot island vibes, get in the mood by creating some Caribbean colour at home

Travel quiz: do you know your aviation lingo?

Consider yourself a bit of an AV whizz? Put your knowledge to the test with our cryptic quiz

My Club: the baker to the stars

Entrepreneur and baking goddess Mich Turner tells The Club what she’s been working on and reveals her future travel plans