THE FLASHBACK • September 2023

The story of Concorde in eight objects

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the first ever non-stop supersonic passenger flight across the Atlantic in September 1973, we asked our resident history custodian, Jim Davies of the Speedbird Heritage Centre at British Airways HQ, to run through some of his favourite Concorde factoids. Take it away, Jim…

The seat

Project Rocket – the nickname given to the interior cabin upgrade of our, then, seven Concordes in 1999 – was placed in the hands of London-based design agency, Factory Design, and one Sir Terence Conran. New seats were constructed with carbon fibre, titanium and aluminium and covered in ink-blue Connolly leather and fabric, with a footrest and contoured headrest. They were inspired by Conran’s chair-making heroes, Charles and Ray Eames, and had the Speedmarque incorporated into the arms. They were thinner-looking and 20 per cent lighter than before and marked the single most significant contribution to the project’s ambition of bringing the elegance of the outside of the aircraft inside.

The blade

This is a blade from one of the four Rolls-Royce Olympus engines that were strapped to the underside of the unique slimline delta wing of Concorde. The power was phenomenal. With a reheat system bolted on the rear, they each produced 38,000lb thrust at take-off – nearly four times that of the original version fitted to the Cold War Vulcan bomber – pushing passengers into the backs of their seats like nothing ever experienced before on a civilian aeroplane. Given that current supersonic airliner developers are struggling with engine design, Concorde’s Olympus engines were yet another remarkable achievement.

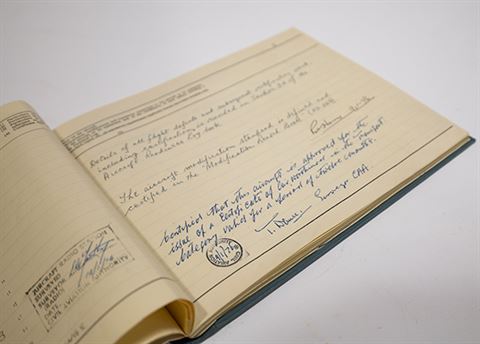

The book

The logbook is key to an aircraft’s overall stash of documentation. This one here is from G-BOAA, our first ever Concorde, which operated the first commercial supersonic service to Bahrain on 21 January 1976. The aircraft flew on that auspicious first day as BA300, under the command of Captain Norman Todd. The endorsement on page three by the surveyor from the Civil Aviation Authority is dated 9 January 1976 and certified that G-BOAA was “approved for the issue of a Certificate of Airworthiness in the transport category valid for a period of 12 months.”

The menu

Concorde menus became much- prized souvenirs of supersonic travel, incorporating a certificate to affirm that the customer “had travelled at Mach 2 in the world’s first supersonic passenger aircraft.” This 1984 menu included a summary of Concorde’s supersonic achievements and a series of questions and answers about the aircraft. High-quality meals with an extensive range of wines, cocktails and aperitifs all complemented the Concorde experience.

The probe

Concorde cruised at Mach 2 (twice the speed of sound) at 58,000 feet. This is the equivalent over the ground of about 1,350mph, or one mile every 2.75 seconds. The pitot-static head probe extended from the pointed nose of the aircraft and cleaved the air ahead of its beautifully streamlined forward fuselage, providing airspeed and altitude data. The air temperature would have been around -60°C, but air friction would have heated the probe to 127°C, but no hotter, or the pilots would have had to reduce speed to stop things melting.

The dish

This English fine bone china butter dish is decorated with a repeating abstracted droop-nose Concorde motif printed in olive-green on a band of blue and bordered in gold. As part of a set specially created for use on our Concordes from 1976 until 1983, the decoration, shape and pattern were designed by Malcolm Keen for Royal Doulton.

The point

The radome, mounted at the front of the Concorde’s hinged nosecone, houses the weather radar scanner and is set at the apex with the standby pitot head. The nose of the aircraft, including the radome and the protective visor shielding the pilots’ view forward, would ‘droop’ five degrees on take-off. On landing, however, the droop would be some 12.5 degrees in order to give pilots a clear view to the landing runway. You can see a Concorde radome, surmounted by a pitot tube, in the Concorde Room on the mezzanine level at Heathrow Terminal 5.

The reg

Every commercial aircraft carries its registration and ownership on a steel plate inside the passenger cabin, frequently at the rear. This plate is from our first Concorde (G-BOAA), which is now on display at the National Museum of Flight in East Lothian, Scotland

This article has been tagged BA, Technology

More from previous issues

A new bar and more bliss: inside Heathrow’s Galleries T5B Club Lounge

Possibly one of Heathrow’s best kept secrets, this lounge has welcomed the arrival of a bespoke Whispering Angel bar – and the updates don’t stop there

Eight things you didn’t know about our Global Learning Academy

We’re pulling back the curtain on our state-of-the-art training facility in this exclusive behind-the-scenes tour

The best of BA news

Donate Avios to charity, book on to our latest route, and check out the newest beverage heading to 35,000 feet

Five nature-tastic epic drives to double your Tier Points

Climb through the Tiers as you soar along the highways in some of the world’s most beautiful places